Black-billed magpie Pica dries her feathers after bathing. Courtesy photo: New Mexico Wildlife Center.

How wildlife handles the extreme heat in New Mexico

By Rachael Brunton

In the world of birds, things are starting to slow down after spring migration, but their rest does not last for long. Birds have mated or are trying to look and sound their best to acquire a mate, and they may be already raising young chicks or waiting for their appearance. Compared to migration for species that partake, simply raising a nest sounds much easier than migrating and not as energy taxing, but that is not always the case. Producing eggs, building and protecting a nest, foraging or hunting to provide nutrients for young that eat so frequently, all while existing in the heat of New Mexico, is a challenging feat. The summer heat in the Southwest can be cruel to even the best adapted animal. Especially in the warmest months in the Southwest, lack of freshwater can be devastating to wildlife—and humans for that matter. Whether it be due to pollution, invasive species, or the climate crisis, learning about native wildlife in our backyards, how they handle the heat, how they utilize and depend on freshwater sources, and how we can create and encourage resources and habitat for wildlife in our own yards is the beginning steps for citizens to change our country’s approach to protecting our most valuable assets, water being one of the most valuable.

Plentiful water provides such obvious benefits for both humans and wildlife; without water, there is no life. Riparian habitats may be the best representative of water supporting life. According to Audubon Southwest, southwest riparian habitats support more than 100 state and federally listed threatened and endangered bird species, and they are home to the highest density of breeding birds in North America. During migration, wetlands and riparian habitat are highly sought after stopover sites for thousands of birds. To name a few, sandhill cranes and snow geese flock to New Mexico’s freshwater resources from the north, specifically relying on the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge and the Rio Grande Corridor. In the summer, wetlands are a hotbed of activity for waterfowl, songbirds, hummingbirds, and raptors resting in the warmer hours, while active in the early morning or evening.

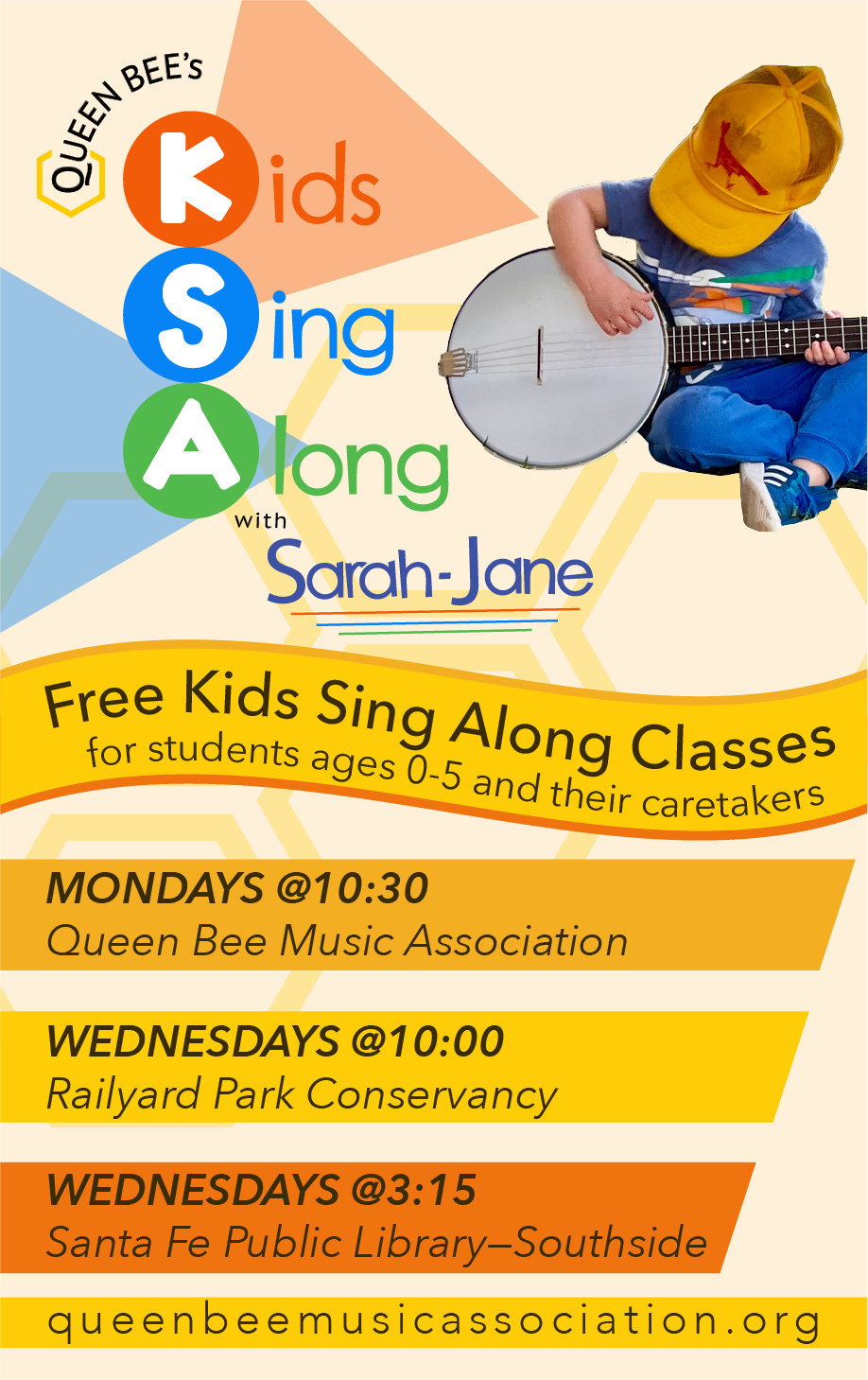

Courtesy photo: Bald eagle ambassador Dyami takes a bath after a training session. Credit: New Mexico Wildlife Center

Outside of choosing to be active in the cooler times of the day, and without the ability to sweat for cooling effect, birds are equipped with other physical qualities and behaviors to adapt to heat, and we can see these at play almost any day in the summer. Some birds practice gular fluttering, almost mimicking a dog panting as their mouth is open, they breathe in and out rapidly, and as air exchanges and evaporates over moist membranes, a cooling effect is produced. You can see birds bathing, dipping even their head in the waters, and after, perching in a safe spot with feathers fluffed, allowing air to pass over wet feathers and cool them in effect. As feathers keep heat in during winter months, they can act in reverse by keeping heat out. The raven, with its black plumage, seems an interesting choice of color in a desert. This black color does draw in the sun’s rays, but concentrates the warmth to the surface of the feathers. As they fly or a breeze comes by, the warm surroundings are simply blown away. Typically seen with vultures, urohidrosis—or urinating on one’s own bare legs—has a cooling effect through evaporative cooling. However, in the hot sun, nothing can replace the availability of clean water for wildlife.

Providing a shallow bath of water for your backyard birds (and cleaning it frequently) is a simple way to support your local wildlife. Planting shade-producing native flora in your yard will encourage birds to rest at a cooler perch. Awareness of local activism and legislation helps protect those freshwater sources we cannot replace. This protection is not only for the direct benefit of wildlife, but for humans as well. If you have ever woken up on an early morning in May, put on your hiking boots, grabbed your camera, and taken a stroll along a river, stream, or bosque, you have directly benefited from the incredible beauty that freshwater provides. It nourishes not only our bodies but our souls. On larger bodies, you can see an osprey steep down head first to grab its prey where only moments before it breaks the water, it flips its talons to the water’s surface and plunges into it to grasp its prey. In quiet streams, you can see a belted kingfisher performing its well-known flight pattern as it patrols its territory and looks for a suitable nesting sight on the bank. So many other witnessings of wildlife living their most successful and beautiful lives can be seen by freshwater.

Courtesy photo: A pied billed grebe patient in the hospital paddles around in the water. Credit: New Mexico Wildlife Center

Outside of the need for water for cooling effect, the need for constant water for daily survival for invertebrate species, fish, semi aquatic mammals, and other water reliant animals, is huge. Conserving habitat like the Rio Chama, Rio Grande, and Pecos River, habitats right in our own backyards, protects an outstanding amount of wildlife. A single individual may have the impression that they can’t contribute effectively to improve conservation efforts for our wildlife, but with beginning in our own backyards and conserving our immediate habitat and wildlife, we can be successful bringing awareness to our neighbors and aiding wildlife that seek safe keeping on our property.

At New Mexico Wildlife Center, our hospital sees hundreds of wildlife patients every year, and we are the home to multiple ambassador animals. Providing water and shaded spaces for the animals is not groundbreaking, but nonetheless it is essential for the care of our animals. Often, after a training session in the summer, after flying with a trainer, or even after purposefully sunbathing, the birds will often seek out their water dishes and perform the most awkward baths, but also the most satisfying I’m sure. After receiving an intake in the hospital, hydration is always a focus. We have an obligation to conserve and improve our freshwater for all wildlife, not just for myself and many other New Mexico residents, but also the wildlife we care for at NMWC. Through only working together with individual residents, legislature, native tribes, conservation groups, farmers, and landowners will we make progress for the animals and humans that rely on freshwater.

If you find yourself around Espanola, you can drop by New Mexico Wildlife Center Tuesday through Sunday from 9 to 4 and learn about native New Mexico wildlife. You can also see how our non-releasable ambassadors cope with the heat in their enclosures, and what we as caretakers can do to help.

Rachael Brunton is the senior raptor trainer at New Mexico Wildlife Center. She and the Education department cares for and trains the Ambassador animals at the Center. Rachael is passionate about the wildlife in New Mexico and loves to educate the public about threats they face today and how we can be good stewards for conservation.