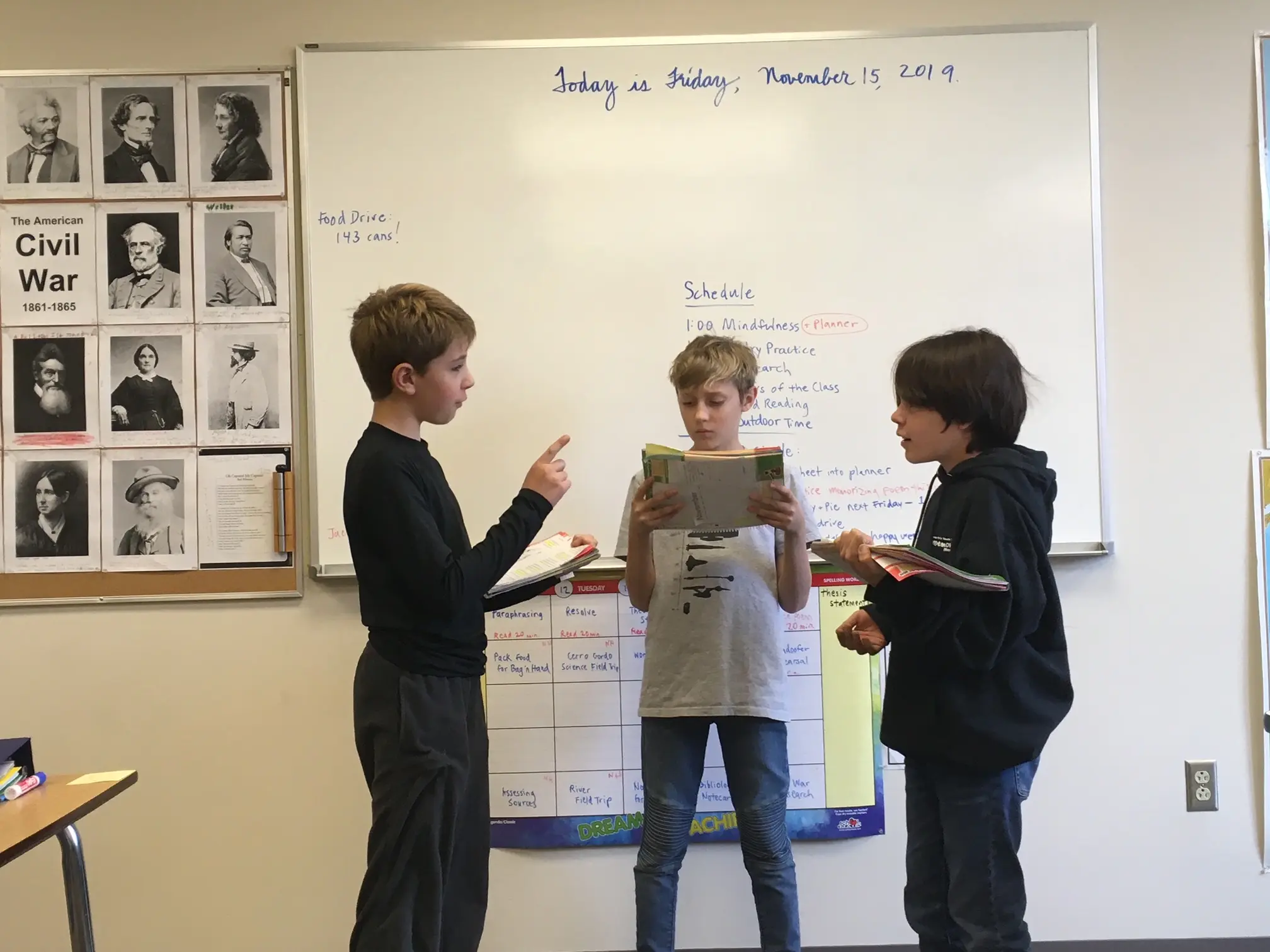

Courtesy photo: Middle school students work together on assignments.

Understanding and empowering our different learners

By Megan Rosker

Children carry an innate curiosity about the world. It’s our responsibility as adults to fan that spark into a flame—fueling enthusiasm, engagement, and the skills they need to meet the world and share their unique perspective.

For the one in five children with dyslexia, that potential can be hidden beneath layers of adversity as they navigate an educational system and culture not built for their brains. Across New Mexico, these children are bright, creative, and capable—but too often misunderstood, misdiagnosed, or overlooked.

Dyslexia is a neurobiological difference affecting how the brain processes written language. It is not a vision problem, a sign of low intelligence, or the result of poor instruction or effort. Many children with dyslexia have average to above-average intelligence and work extraordinarily hard in the classroom. Dyslexia often coexists with other learning differences like ADHD or dysgraphia and presents uniquely across ages. Early identification and intervention are essential.

According to the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, dyslexia affects about 20 percent of the population and accounts for 80–90% of all learning disabilities. In a typical classroom of 20 to 25 students, about four to five may be navigating school with a dyslexic brain. Yet many parents and teachers are unprepared to recognize symptoms, know how to refer students for testing, or implement specialized teaching techniques. Because dyslexia exists on a spectrum, many cases go undiagnosed, with individuals developing coping strategies to manage.

One persistent myth is that dyslexia means reading words backward. While letter reversals can occur, dyslexia is more about difficulties with phonemic awareness—the ability to hear and manipulate sounds in words—and challenges in spelling, handwriting, memory, and reading fluency. Dyslexic students often put extraordinary effort into keeping up with rapid language acquisition demands.

Another myth is that children will grow out of dyslexia. Without systematic teaching of foundational language principles—regardless of language—children with dyslexia do not outgrow their challenges but often grow more frustrated.

A further misconception is that bilingualism worsens dyslexia. Research from the International Dyslexia Association and journals like Annals of Dyslexia and Frontiers in Psychology shows bilingual children with dyslexia have the same core challenges as monolingual peers. However, bilingualism can strengthen cognitive skills such as executive function and metalinguistic awareness. Teaching foundational language skills—like phonemic awareness and decoding—in any language helps dyslexic learners improve reading and writing. In New Mexico, where many children speak Spanish, English, and Native languages, embracing foundational multilingual skills supports identity and motivation, enhancing learning outcomes rather than hindering them.

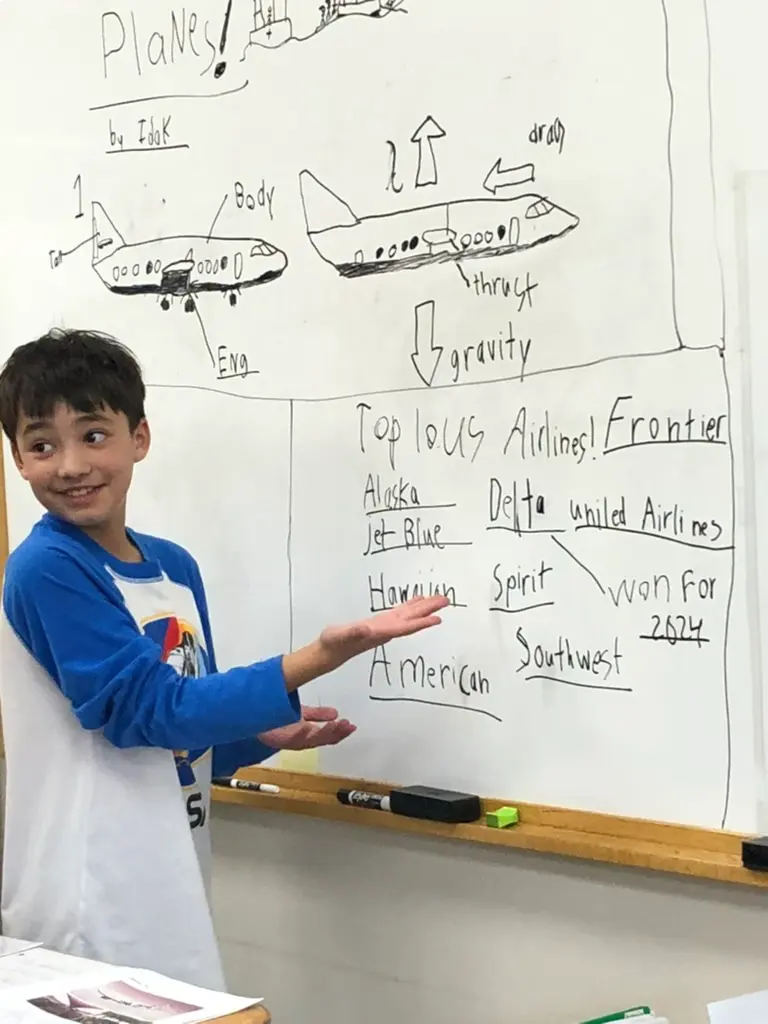

Courtesy photo: Idak Fierro shares his personal interests in planes at the white board during a typical day at May Center.

Perhaps the most damaging myth is that dyslexia reflects low intelligence. History shows that many brilliant minds—like Albert Einstein, Agatha Christie, and Steve Jobs—had dyslexic traits.

Reading is a relatively recent cultural invention. Unlike spoken language, which humans have used for tens of thousands of years, widespread literacy emerged in the past few centuries. Universal education systems took hold in the 19th and early 20th centuries, including in New Mexico, where many Native languages were traditionally oral. Formal schooling after statehood in 1912 emphasized English literacy and often suppressed native languages.

Research shows that oral traditions—storytelling, song, poetry—are vital for dyslexic learners and often areas where they thrive. Teaching foundational language principles, including phonics and sound manipulation, is critical. These elements combined create truly literate students, whether learning English, Spanish, or Native languages.

This shift from oral to print culture has outpaced the brain’s evolutionary development. Reading requires rewiring the brain, engaging areas for vision, language, and memory. Since not all brains are wired alike, assuming reading fluency is universal creates challenges for many learners.

Literacy today demands much more than reading basic text. Individuals must navigate complex written and visual information across multiple media. This raises the stakes for young learners and highlights why understanding individual differences in reading processing is vital.

The dyslexic brain works differently. Brain imaging shows dyslexic readers use different brain areas—those better at big-picture thinking, visualization, and making creative connections—rather than the linear decoding centers most people use. This can make reading effortful but enhances strengths in holistic thinking, 3-D visualization, and pattern recognition—skills valuable in engineering, design, entrepreneurship, and problem-solving.

Historically, before literacy norms, societies valued oral storytelling, memory, and spatial navigation—areas where dyslexic thinkers excel. As AI automates routine tasks, human creativity, insight, and adaptability—strengths of dyslexic minds—become increasingly essential.

Public schools increasingly screen for dyslexia and provide intervention services. Pediatricians can recommend further testing, and some insurance plans cover evaluations, aiding early diagnosis. Families can access resources through SWIDA and The Reading League NM for support tailored to their needs.

Shifting the dyslexia narrative from deficit to difference fosters inclusion and empowerment. With proper support, children with dyslexia can thrive. A growing community of parents, educators, and advocates in New Mexico works to ensure these learners receive opportunities—not just accommodations.

Our children deserve to be seen for their complexity and brilliance. Understanding dyslexia deeply opens the door to a future where every learner is honored and empowered.

Courtesy photo: Developing skills in any language requires student engagement on many levels.

New Mexico Resources

Families and educators in New Mexico are supported by the following organizations:

- Southwest International Dyslexia Association (SWIDA) offers education, advocacy, and workshops for families and educators.

- The Reading League NM provides resources and training on evidence-based reading instruction.

- The May Center for Learning offers individualized instruction and professional development rooted in the multisensory Orton-Gillingham method, effective for dyslexic learners.

Mark Your Calendar

Join the Dyslexia Justice League Conference on Friday, November 8th, at the May Center for Learning in Santa Fe. This event offers parents, educators, and experts a day of learning and connection to better support dyslexic students.

Megan Rosker is the director of outreach and admissions at the May Center for Learning and a literacy advocate dedicated to empowering students with diverse learning profiles across New Mexico.